Shanel Wu

They/them. PhD student: smart textiles, weaving, computational craft, hardware hacking.

Random Combination Generator

Spring 2022

Summary

A simple web app that I made as a classroom tool, which helped students generate novel connections between concepts from different course topics. Because the instructor (for whom I was the TA) and I couldn’t find a tool that did exactly what we wanted, and I decided it was easier for me to code my own than to continue looking for one/a few to hack for our purposes.

The main ingredients:

- JavaScript (with JQuery)

- HTML/CSS

- .TXT file data

- Firebase Hosting

Instructional Use

A detailed account of how this tool was used during our class sessions, and further context on how it served the teaching goals for the course.

The Course

During the SP2022 semester, I was the graduate TA for ATLS2000: The Meaning of Information Technology. This introductory-level course surveys the history of information/communication technologies (ICT) and contemporary issues of ICT applications on humans such as social and political change, psychological and cognitive effects, and environmental impacts. It covers a lot of topics.

Each week focuses on a different topic, and with material covering everything from the history of computers, to the influence of algorithms on existing social biases, to the future of work – there’s not much time week-to-week for students to synthesize information between topics. Exams, like the midterm, actually offer an opportunity to “integrate” the weekly units because students are reviewing while they study anyway.

Classroom Activity - Part 1

The planned instructional activity was part of the course midterm. Part 1 of the activity divided the students into small groups of 3-5 and assigned a weekly topic to each group. We shared a Google document to all the groups to edit simultaneously. To prevent this process from being complete chaos, the document was already set up with one single page (with pagebreak) per group, their assigned topic, and a blank table where they would enter their responses.

In these groups, the students recalled the terms and concepts discussed in that week’s content and wrote brief definitions for each. As this part of the “in-class midterm” was designed to generate the data for the combo generator web app, we required the students to format their lists of terms and concepts like so:

Idea / Key Term

Definition

<term or concept 1>

<short definition, 1-3 sentences>

<term or concept 2> <short definition, 1-3 sentences>

<term or concept 3 and beyond…> <short definition, 1-3 sentences>

As an example, here is an excerpt from a student list of key terms and definitions for the weekly topic, “Black Box of Algorithms”:

Black Box of Algorithms

Idea / Key Term Definition

ADT (AWS) Automated decision systems, spin-off: automated weapons systems for robotic warfare technology. Often used because we do not want to make decisions that include many factors

Black Box of Algorithms The idea that a company creates an algorithm for another without the end user knowing how it functions and what factors it uses

Big Data The multitudes of data associated with multiple aspects of people and group’s interests, demographics, and history

Once the students had completed their lists of terms/definitions for their topics, we compiled the lists into a carefully-formatted plain-text (.TXT) file. At this point, we took a brief (10-15 minute) break for class, which gave us time to push the updated .TXT file to the server, populate the random generator tool with the students’ work, and troubleshoot any minor typos or glitches with the web app.

Classroom Activity - Part 2

Here’s where the students actually used the tool. With all of their combined work, all the weekly topics and every group’s list of terms, the generator web app would show random combinations of two terms from different weeks, with their definitions, and ask the students to explain how they thought the two concepts were connected. This comprised the remainder of class time. Students viewed and/or filled out as many combos as they felt appropriate, until they had their top three connections to submit for the graded assessment. To give a better idea of the different topics that students were connecting, the weekly topics were:

- Week 2: “Computers and Thinking Frameworks”

- Week 3: “Internet and Net Neutrality”

- Week 4: “Black Box of Algorithms”

- Week 5: “Diversity and Representation”

- Week 6: “Digital Divides and ICTD”

More on the actual interface in the next section.

Interface Design

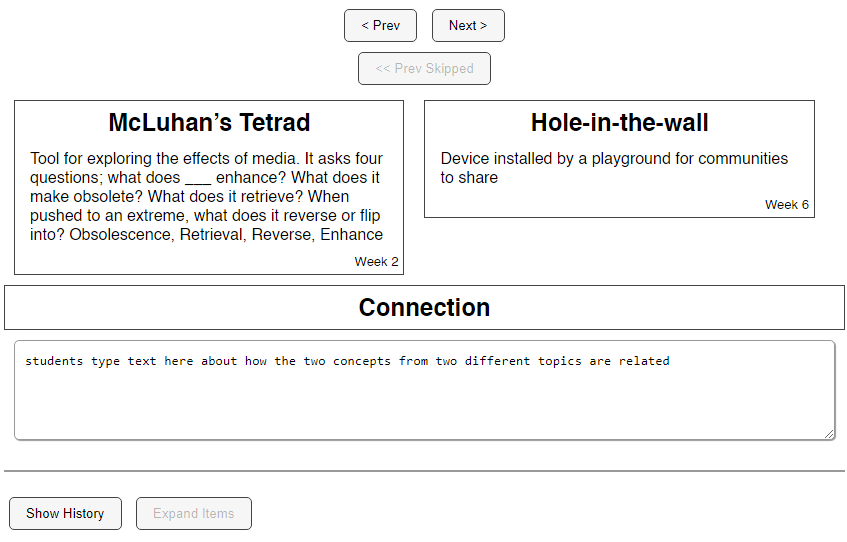

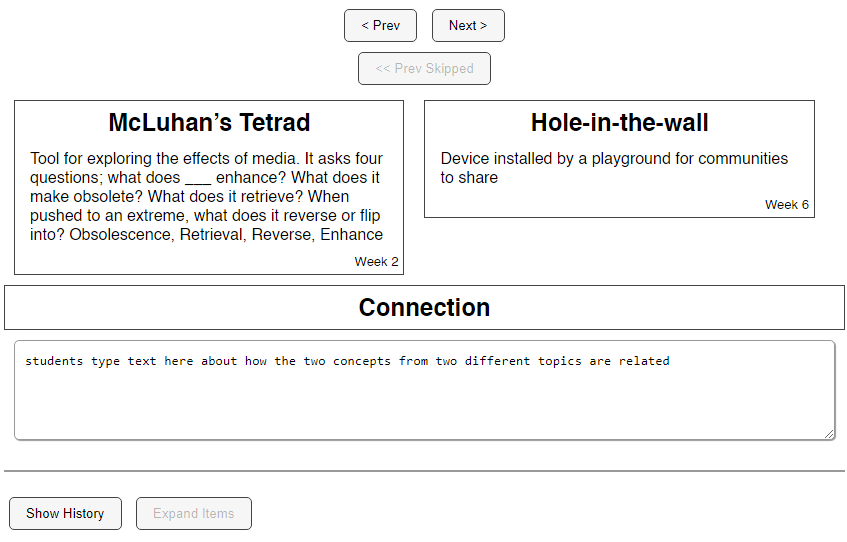

Here’s a more thorough walkthrough of the web app’s interface as a student would have seen it during the classroom activity.

Because we had the class divided into two sections that would attend class on different days (and thus, two different datasets of terms and definitions), the student first selects their course section on the welcome prompt.

Then, they are taken to the main interface, which would show a random combination of two terms from different weekly topics. The terms are shown as “cards” with the term on the top line, its definition in the center, and the week in the lower-left corner (which also lets us verify that the combinations are being properly generated).

Below the cards, the student would type their explanation for the connection between the two terms in the given text input area. Above the term cards, the student can change the displayed combo by clicking the “next” or “previous” button. Generally, the “next” button will show the student a new combo with two different terms. If the student has already seen multiple combos, the “previous” button will let them scroll back through previous combos, all the way until the first one. If they are viewing a previous combo, the “next” button will let them scroll forward within their history until they reach the most-recently generated combo, after which the “next” button will resume showing them new combos. If the student leaves the connection text blank, and goes to view a different combo, the one they were previously viewing will register as “skipped”.

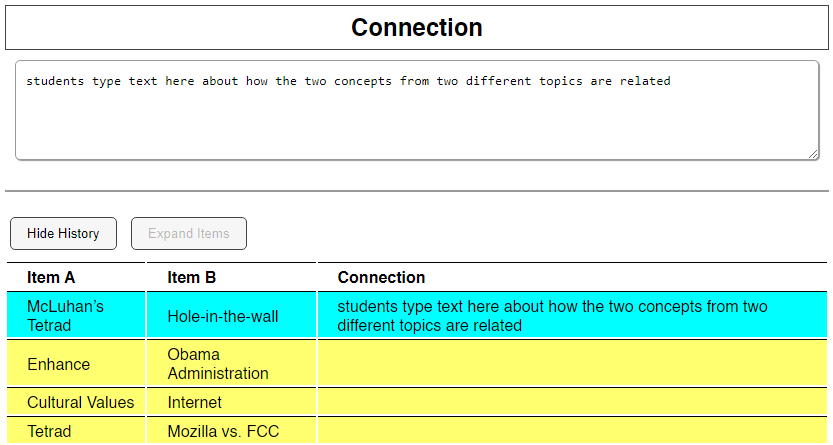

As the student progresses through more combinations, they can view the entire log of their session by clicking “View History” below the text input area. This will open an alternate view of the concepts and connections, displaying them in a table rather than one at a time.

The combination that is currently displayed above is highlighted in blue. A combination highlighted in yellow indicates that the student had skipped it.

Technical Implementation

Because the whole goal for making this tool was getting the most function (and the minimum viable prototype) in the least amount of time, I used the environments I was most familiar with, which is client-side JavaScript embedded in HTML/CSS. The full list of components:

- JavaScript (with JQuery)

- HTML/CSS

- .TXT file data

- Firebase Hosting

“Function” in this case also included the ability to quickly get student responses into the the source code, as well as the ability to get the tool in front of students’ faces. For the former, I had a hunch that I could get some sort of raw text blob served with the webpage content, hence the .TXT file to act as an intermediate format between the class Google doc and the text data. For hosting the web app, I had recently learned how to properly use Firebase, and I felt comfortable enough with the platform to deploy changes to a hosted app while also running a class.

I want to try writing more about my coding and other technical processes, so I’ll break down my logic further for some specific sections of the code. You can find all of the app’s assets in this GitHub repo. I’ll mostly be referring to the JavaScript file, script.js. [LINKS]

.TXT File Loading and Parsing

The first open question I had to solve was, “How do I get a .txt file into JavaScript?” Luckily, I found this StackOverflow question from a user trying to do the same thing. Keeping things simple and hacky, I used the top answer’s hack of including the text file in a hidden HTML <iframe>. From the HTML element, the JS code could then execute a bound function loadFile(), that extracted the text file’s contents as a gigantic string. It’s not the most efficient way to do it, and since I was already using JQuery, I could have also used AJAX, but I’m just more experienced with grabbing absurdly-nested attributes from the DOM.

Next, once the .TXT had been loaded, the code had to parse its contents to populate the app with the students’ responses, and to properly generate random combinations of these responses. The careful formatting from Part 1 of the activity was crucial here; my not-so-smart code needed the weekly topic headings, key terms, and their definitions to all be consistently separated and ordered, or else the displayed data would be unusable. The longest function in my code (30 lines compared to 20 or less for the others), parseData(), handles this logic, and you can find a much more thorough explanation in the code walkthrough.

Helper Classes: Item and Combo

To structure the data once it was parsed, I created two classes that represented the main units of the activity: Item (a key term) and Combo (an associated pair of Items).

The Item class is purely an object that stores the attributes of a key term contributed by students. With the key term as the object’s name, each Item also has an arbitrary id number, which weekly topic it came from (keyed by the week number), and the key term’s definition (def). I didn’t need to write any methods for this class.

The Combo class primarily stores a link between two specific Items, with some extra convenience functions.

“Random” Generation

As a result of the parseData() function having executed, the program should have a large dataset, choices, consisting of Items that are separated by the week they belong to. The generateCombos() function runs at this point, and its goal is to generate a list of all the possible combinations of Items. It starts by making a list of each possible pair of weeks, since our classroom exercise defines a valid Combo as a pair of terms/concepts from two different weeks (2-6). We wanted students to have to explain connections between a concept from week 4 and one from week 2, a combination of week 3 and 6, etc.

I should note that order doesn’t matter with these week pairings. Representing a pair as a two-number list, the pair [4, 2] means exactly the same thing as [2, 4], so the list of pairs only includes one of these representations to avoid duplication.

Once each pair of weeks had been listed out, generateCombos() then proceeds to list out all the possible Combos from the Items in each week pairing. In other words, for the generic pair [a, b], week a has its set of associated Items and likewise for week b. We want all the possible combinations of itemA and itemB from weeks a and b respectively. Like with pairing the weeks, order doesn’t matter – connecting itemA to itemB is the same as connecting itemB to itemA.

Once generateCombos() is done, we have a massive list of Combos to choose from, which is stored in the comboChoices array. When we ran this activity, students generated about 15-20 key terms for each week. Roughly estimating how many combinations this generates, we start with the fact that there are 5 * 4 = 20 pairings of different weeks. Even if we underestimate that students could only generate 10 key terms per weekly topic, each week pairing would still have 10 * 10 = 100 possible Combos, for a total of 20 * 100 = 2000 combinations of terms to choose from. Our actual numbers: one section of the class generated 6,873 Combos, and the other generated 11,720 Combos.

There hasn’t been anything mathematically sophisticated here, and that will stay true as I describe the crude way that Combos are selected in the pickCombo() function. I just used the built-in Math.random() function, which gives a PSEUDO-random decimal number between 0 and 1. I gave myself two helper functions: randomUpTo(x) which gives me a random whole number between 0 and x; and chance(percent) which essentially simulates a random dice roll or coin flip which returns true some percent of the time. Then, pickCombo() just needs to pick a random number between 1 and the length of comboChoices (i.e. randomUpTo(comboChoices.length)) and pick the Combo at that position in the list. To keep the UI display more randomized, the selected Combo will sometimes swap the order of its two items when displayed (i.e. if chance(50) returns true). To avoid duplicating a previously-chosen combination, the selected Combo gets removed from comboChoices and added to the user’s history.

Possible Improvements

I attempted to somewhat order these starting with the most urgent or easy-to-do.

1. Enabling general use by anyone

As of summer 2022 (the version used in class), the student-generated text data is still hard-coded into the web app. I won’t always be the grad TA to push a new text document to the server, so there’s some work to do in order for the instructor to easily use the combo generator in future semesters. I think I’ll need to tweak some of my infrastructural choices, especially the .TXT file hack.

Ideally, the instructor would only have to send out one single link for the whole classroom activity. Not a Google doc link, then the link to the combo generator. Seems like this could be easily done by generating some sort of “session ID code” for each time the activity is run, which is then stored in a database and given a container for associated data. All of the student-generated data could then be stored directly in the database, in the session’s container. This would also solve the convoluted process for populating the combo generator: convert the student data from one text document to another, manually double-check that all of the data is properly formatted, then parse the giant data blob.

A new procedure to handle separate sessions and take in student data also implies changes to the existing interface (or more likely, adding new interfaces). What those changes would look like is saved for the next section. But on the back end, this might also mean that I should redo the tech stack to convert the tool from an overly-fancy JQuery form to an actual progressive web app (PWA) built with an appropriate framework.

2. Interface improvements

From student feedback:

- make the “swap” function a button for the user

- other functions that influence the combinations displayed, like focusing on a particular weekly topic

- making sure UI components don’t jump around with different size

Itemcards because some terms/concepts have more text to display - actual instructions on the page

NEW interfaces for general usage:

- welcome interface for instructors

- password-protected? (if I’m still hosting the app, then I don’t want random people using up my storage, so I would personally give send someone the designated “instructor role” password)

- starting a new session

- generate a session ID

- set an instructor password (so students can’t change things about the session)

- setting the concept categories (like weekly topics in our class), the categories that students will be trying to make connections across

- assigning students to groups and/or assigning groups to categories

- a “start session” button

- continuing existing session

- welcome interface for students

- entering session ID (if they’re not coming from the pre-generated link)

- selecting which group they’re in that session

- seeing their assigned topic OR choosing their topic (depending on instructor config)

- in-session interface for instructors

- controlling if the session is in phase 1 of the activity (students inputting terms/concepts and definitions) or phase 2 (students making connections)

- in-session interface for students

- phase 1

- phase 2 (exists, described on this page)

3. More interesting features/interactions

4. Memory/storage efficiency

References

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/4533018/how-to-read-a-text-file-from-server-using-javascript

- https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Global_Objects/Math/random

- https://www.iflexion.com/blog/progressive-web-app-framework

Obsidian Links

[[programming]]